The Failure of the Arab Spring - Soft Power and Soft States: Author Article by Lyric Hale

posted by Lyric Hughes Hale on March 13, 2012 - 12:00am

In the next instalment of her regular column, top economic commentator and What’s Next? author Lyric Hale discusses social media and its new role as a catalyst for political movements. Looking in particular at the failures of the Arab spring, Hale highlights the difficult realities that lie behind the twitter rhetoric.

Author Article by Lyric Hughes Hale

By now, tens of millions have seen the viral video about Joseph Kony, the leader of the Lords Resistance Army, but one has to wonder how much good this media attention will bring to the tragic lives of his Ugandan victims. Call me cynical, but it does amuse me to hear people suddenly spouting off about Ugandan politics, who couldn’t find it on a map a week ago. As if ridding the world of one bad guy will make things better. As if knowing something is the same thing as doing something about it.

I suspect that however despicable, Kony might be a paper tiger. He is a minor warlord with as few as 200 followers, who is no longer even in Uganda. According to Reuters, a UN spokesman said of some recent violence attributed to the LRA, “We think right now it’s the last gasp of a dying organisation that’s still trying to make a statement”.

Experts on the ground say that Uganda is no longer at war, and is now beginning a period of reconstruction and rebuilding. There is excellent commentary in the Guardian by Polly Curtis, which gives a more nuanced view of the situation. She quotes Ugandan journalist Angelo Opi-aiya-Izama, who explains why the US is interested, and has sent a hundred advisors to assist the Ugandan army:

“One salient issue the film totally misses is that the actual geography of today’s LRA operations is related to a potentially troubling ‘resource war’. Since 2006, Uganda discovered world-class oil fields along its border with DRC. The location of the oil fields has raised the stakes for the Ugandan military and its regional partners, including the US. While LRA is seen as a mindless evil force, its deceased deputy leader, Vincent Otii, told me once that their fight with President Yoweri Museveni was about ‘money and oil’. This context is relevant because it allows for outsiders to view the LRA issue more objectively within the recent history of violence in the wider region that includes the great Central Africa wars of the 90s, in which groups like LRA were pawns for proxy wars between countries. In LRA’s case, its main support came from the Sudanese government in Khartoum and many suspect it still maintains the patronage of Omar el-Bashir, the country’s president, himself indicted for war crimes by the ICC.”

So the game is oil, and the removal of Kony is not going to change a high-stakes conflict. Oil of course is a key element of current conflicts in the Middle East. The Arab Spring, like the Green Movement in Iran before it, did nothing to change the dynamics of power in the region, and might have actually made life worse for many.

The Cult of Personality

In a global celebrity culture, it is seductively easy to understand a highly complex situation by demonizing a single person. We did that with Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and before that with the Shah in Iran. Was the change positive? For Iran, absolutely not. In Iraq? A never-ending nightmare with a disputed number of casualties, but 5 million orphans as reported by the Iraqi government. In countries that lack strong institutions, a change of leadership seldom presages a positive change in direction, just new actors doing the same play. A book which will be published by Yale University Press next month, explains why change is so difficult.

The Battle for the Arab Spring is an absorbing country-by-country overview of what happened in 2011, written by two authors, Lin Noueihed and Alex Warren, who were actually there and see no reason for surprise:

A new chapter perhaps, but not a quick solution to the region’s problems, as the authors discuss:

A year on, there is much to suggest that the Arab Spring should have been predictable. A media revolution prepared the ground. Elite corruption was insulting to ordinary people who struggled with soaring food costs, rising rents and miserable job opportunities. Strikes were breaking out. Protests were increasingly common. Yet in 2010, right on the eve of change, plenty of evidence suggested that regimes in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and elsewhere were impregnable, that popular protest could never achieve anything, and that talk of ‘Arab exception’ was perhaps true. Few realized that a new chapter in Arab history was about to open.

In the absence of democratic institutions, a nation’s wealth is allocated to special interests, through a process we call corruption. The bounty created by natural resources and privatization is siphoned off to privileged players, often the families of those closely connected with the government. If the head gets chopped off, the body sputters momentarily, but soon a new mouth begins to feed.

Soft States Are Persistent

Syria

In a culture of dictatorship and weak institutions, removing a dictator or their henchmen will not likely create change. A case in point: Syria. If Bashar al Assad steps down, anyone who thinks that this will make things better is most likely mistaken. As Valerie Szybala, a Syria specialist writes in Policymic:

It is difficult to imagine a Syria without the Assad regime. Syria has no real political opposition, no experience with democracy, and lies in a region flooded with destabilizing transnational organizations such as Hezbollah. Not even the current protest movement is organized or unified enough to provide a realistic alternative to the current government, nor have they presented any vision of a post-Assad Syria.

There are few silver linings in the context of Syria’s revolts. The Assad regime is bad, yet it is easy to imagine something even worse than a secular (and formerly predictable) dictator. What if Syria collapses into a bloody sectarian civil war? Or what if the government is taken over by hardline Islamic fundamentalists?

Social media, which allows fluid association, flat or no leadership, and free dissemination of information, is great for arranging protests. But these characteristics are the opposite of what is needed to create sustainable institutions. Communication can start the process of democracy, but it cannot complete it.

Egypt

The soft state can be persistent. Noueihed and Warren quote Egyptian economist Galal Amin:

The soft state came to Egypt about thirty-five years ago” and had appeared “both totalitarian and soft” since the 1980s, restricting individual freedoms on the one hand but constructing bureaucratic frameworks that by their very nature encourage law breaking on the other.

Post-Mubarak, is life better for the average Egyptian? Most emphatically no, and religious tolerance has actually decreased. Zvi Bar’el of Haaretz.com quotes a letter he received from an Egyptian friend:

At the public level things are degenerating from day to day…Getting rid of the president suddenly seems like a simple task as compared to the uprooting of the culture of dictatorship, which is firmly rooted not only in the government institutions but also in the public. This culture has become part of the prevailing culture over hundreds of years, as has corruption. Now the dictatorship and the corruption are blending with the religiosity and the religious movements, which are in control of every area of endeavor in the country and are building themselves up as the new National Democratic Party [the ruling party under Mubarak], thereby exacerbating the younger generation’s frustration. And the idiot Americans are falling into the trap laid for them by those groups and are beginning to play the same two-faced diplomatic game they played with the brutal regimes of the past, which will lead to a new regional conflagration in the future.

New Dangers

Religious tolerance has decreased as religious-based organizations have moved to fill power vacuums across the region. Christian minorities in Egypt and in Syria will agree that they are more fearful than before the recent uprisings. Even in Tunisia, which seems to be a bright spot, hopes have dimmed as an anti-secularist Islamic group known as the Salafis have appeared to demonstrate and harass, sometimes violently, women, students, intellectuals, journalists, and religious moderates. “We are dealing with the business of government, we have floods in the north, a sinking economy, and these people are talking about the burqa and the hijab” a Tunisian politician told the Associated Press recently.

Loss of US Influence

Caroline Glick, writing in the Jerusalem Post, highlights how the Arab Spring has resulted in “a spectacular loss of influence in the Arab world” not for Israel, but for the United States:

To understand the depth and breadth of America’s losses, consider that on January 25, 2011, most Arab states were US allies to a greater or lesser degree. Mubarak was a strategic ally. Saleh was willing to collaborate with the US in combating al- Qaida and other jihadist forces in his country. Gaddafi was a neutered former enemy who had posed no threat to the US since 2004. Iraq was a protectorate. Jordan and Morocco were stable US clients.

One year later, the elements of the US’s alliance structure have either been destroyed or seriously weakened. US allies like Saudi Arabia, which have yet to be seriously threatened by the revolutionary violence, no longer trust the US. As the recently revealed nuclear cooperation between the Saudis and the Chinese makes clear, the Saudis are looking to other global powers to replace the US as their superpower protector.

Perhaps the most amazing aspect to the US’s spectacular loss of influence and power in the Arab world is that most of its strategic collapse has been due to its own actions. In Egypt and Libya the US intervened prominently to bring down a US ally and a dictator who constituted no threat to its interests. Indeed, it went to war to bring Gaddafi down.

Moreover, the US acted to bring about their fall at the same time it knew that they would be replaced by forces inimical to American national security interests. In Egypt, it was clear that the Muslim Brotherhood would emerge as the strongest political force in the country. In Libya, it was clear at the outset of the NATO campaign against Gaddafi that al-Qaida was prominently represented in the anti-regime coalition. US actions from Yemen to Bahrain and beyond have followed a similar pattern.

Kenya: Between Hope and Dispair

Yale Press has another wonderful new book, Kenya: Between Hope and Despair, 1963-2011 by Daniel Branch which brings me back to Africa, and to social media. He begins with a brilliant quote by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the celebrated Kenyan author who was himself imprisoned:

Democracy is a really complex phenomenon. It involves the right of a people to criticize freely without being detained in prison. It involves a people being aware of all their rights. It involves the rights of a people to know how wealth is produced in the country, who controls that wealth, and for whose benefit that wealth is being utilized. Democracy involves therefore the people being aware of the forces shaping their lives.

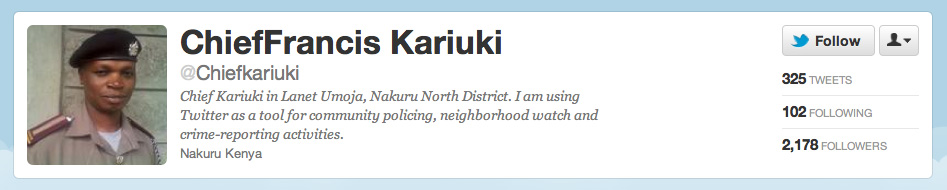

Being aware is the first step. On the book’s blog, there is a mention of a police chief in Kenya who has tried to use twitter to stave off crime in his district:

Twitter does not a government make. If you tweet, send Chief Kariuki a message of support for using whatever tools he has at his disposal to create awareness, and prevent crime. Free speech is a necessary but not sufficient condition to create better government, long-term stability and better economic opportunities in the developing world. We are not talking about a single year, but decades, in order to create sustainable change. The Arab Spring will span many, many seasons.