Does A Weak Yen Really Help Japan?

posted by Richard Katz on February 23, 2022 - 9:54am

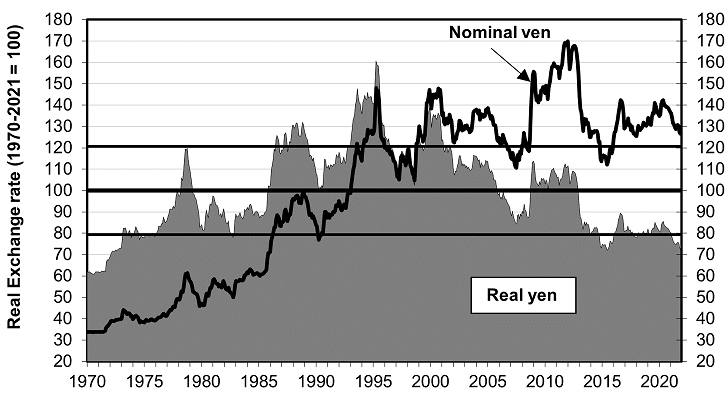

For someone with an injured leg, a crutch is necessary; relying on it for too long atrophies the muscles. Japan’s crutch is the weak yen and it is atrophying Japan’s economic muscles. Today, in “real” terms, the yen is at its lowest level in a half-century. “Real” means adjusting for different rates of inflation in Japan and its trading partners (see figure above).

With the yen continuing to slide downward, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda wants Japan to continue using that crutch. He insists that a weak yen is a “net positive,” even though he admits that “the yen's depreciation might have a negative impact on household income through price rises.” By contrast, Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki has stressed the need for “currency stability,” a statement regarded as a “verbal intervention” to keep it from weakening too far too fast. Rising prices for daily necessities could affect Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s popularity ahead of this summer’s Upper House election.

If Japan only concern were top-line GDP numbers, it might seem as if Kuroda were right. Domestic demand has been so weak that the little growth Japan has eked out has been excessively dependent on a rise in net exports (i.e., exports minus imports). Real (price-adjusted) household income has been depressed by two tax hikes and stiff price hikes in import-intensive items. As a result, personal consumption actually fell by 1% during that seven-year period. Such a long drop is unprecedented in postwar Japan.

A weak yen enables offsets this low domestic demand by enabling exporters to lower their price in foreign markets without losing money. This helps them sell more. As the yen plunged, net exports took the lead in driving growth. From first quarter of 2014 to the last quarter of 2019 (before COVID), Japan’s GDP expanded just ¥7.2 trillion (a measly 0.2% annual rate). Net exports grew even more: by ¥10.7 trillion yen. In other words, without external demand, GDP would have fallen during that period.

A country that needs a weak currency to sell its exports is like a firm that can only sell its products if it keeps cutting prices by lowering the wages of its workers. A healthy economy is like a firm that can sell its products at good prices while raising the wages of its employees. That is the difference between Japan and Korea.

Today, the real value of the yen is 29% below its 2012 level. By contrast, the real Korean won is 7% above its 2012 level. Nonetheless, from 2007, just before the global financial catastrophe, to 2019, just before COVID, Korea’s per capita GDP rose 35%, five times as much as Japan’s 7%.

While Japan relies on a low wage/weak currency strategy to fuel its exports, Korea’s exports are fueled by innovative products and efficiency improvements. Over the period from 2005 to 2019, output per worker in Japanese manufacturing grew 25%, but workers were denied the fruits of that. Compensation (wages plus benefits) rose a negligible 1%. By contrast, in Korea factory productivity grew 57% and workers enjoyed a 52% hike in earnings.

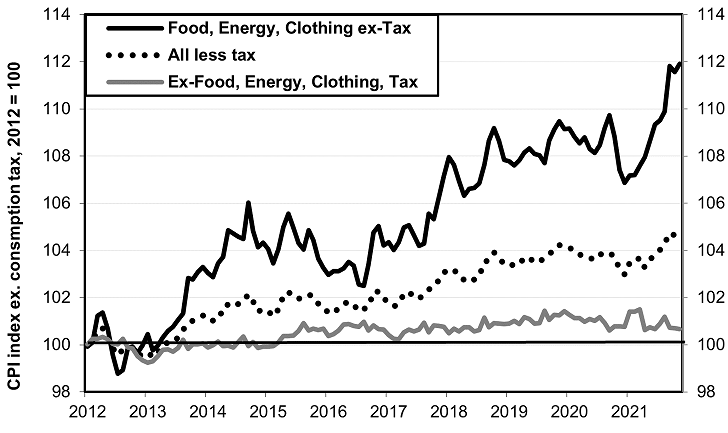

One reason Kuroda is so committed to a weak yen partly is that it has been pivotal to his futile efforts to achieve 2% inflation. What little inflation he has achieved has been “bad inflation.” A weak yen raises the price of imports. Nearly 40% of consumer spending is accounted for by items dominated by imports, including energy, food, clothing, and footwear. Not counting the consumption tax hikes, the price of those items went up by 12% from 2012 to 2021. By contrast, prices for the other 60% of consumer spending rose by 0.7% during the same period. More than 90% of the entire rise in the consumer price index ex-tax was driven by import-heavy items. That’s a transfer of income from Japanese households to foreign producers, just as harmful as an OPEC-induced rise on the price of oil.

At the same time, the weak yen enriched the country’s big multinational companies. In short, the weak yen indirectly transferred income from the Japanese consumer to those big companies. Kishida and his aides have correctly stated that the “trickle down” theory of Abenomics produced very little actual trickle down. Unfortunately, Kishida does not seem to follow rhetoric with any action.