Central Banks, not the Events in Ukraine, are Primarily Responsible for the Current Inflationary Surge

posted by Tim Congdon on March 31, 2022 - 9:51am

Double-digit annual rates of inflation now seem certain in the United States of America, and are also likely in the Eurozone and the United Kingdom, and in other significant advanced countries such as Canada. The explanation for many people – both now and in the future – will be “Ukraine”. Given the horror of what is happening there, that reference is unsurprising. But it is important to remember that – for example – the recently-announced 7.9% increase in the USA’s consumer price index related to the year to February, before Russia’s invasion. “Ukraine” will give mainstream economists – who have been very wrong in their recent analyses of inflation – a bogus explanation for the jump in prices.

The dominant causal influence on the inflation upturn has been the marked acceleration in broad money growth which began, in leading Western economies, in the second quarter of 2020. That has been emphasized in these notes for almost two years now and is reiterated in the latest monthly video. To highlight the role of money in the causation of inflation is not to deny the relevance of the Ukraine catastrophe, as it will add one or two twists to the inflationary spiral. Vladimir Putin is a hate figure and deserves to be blamed for many things. All the same, he is not responsible for the 7.9% US CPI increase in the year to February. (The human suffering is awful and I don’t want to minimize it. But in 2019 Russia accounted for only 1.8% of world output, where such output is measured in current prices and exchange rates, and Ukraine for a mere 0.2%.)

In my latest contribution to The Critic, I recall the inflation upsurge of the 1970s. In a familiar narrative that upsurge is often attributed to the large increase in oil prices in late 1973/early 1974, arising from the Arab oil embargo. But the Arab oil embargo cannot answer the question, “why in the three years to end-1975 did the UK’s consumer prices rise by over 57% whereas in West Germany they rose by a more moderate 21%?”. West Germany and the UK had just the same oil price shock. The crucial difference between the UK and West Germany was that economists in the former were mostly Keynesians who denied that the quantity of money mattered to anything, while economists in the latter had a strong folk memory of the 1923 Weimar hyperinflation and the disasters (the Great Depression, Nazism, etc.) that followed it. The Bank of England allowed money growth of 25% or so in 1972 and 1973, and this excess money growth was the key driving force behind the UK inflation in the mid-1970s. The 20% jump in the German price level in those years was also unsatisfactory, but at least the Bundesbank appreciated that money growth had to be curbed if a comparable setback were to be avoided in future.

I wish I could say that the monetary theory of national income determination were now widely respected in the leading central banks. After all, recent economic history is eloquent enough about its validity. But the top central banks are cavalier about basic principles of monetary economics. First, in the USA the New Keynesians remain in charge of Federal Reserve research and have bamboozled the hapless Fed chair, Jay Powell, into believing that money is no longer relevant to inflation. In the three months to January 2022 the M3 money measure (as estimated by the Shadow Government Statistics consultancy) increased at an annualised rate of 11.2%. US money growth will drop in coming months, but the excess money overhang from the 2019 – 21 period will blight the Biden Presidency. For more detail, see our usually monthly review of money growth developments in the main economies.

Second, money growth is also decelerating in the Eurozone, but this is only after a period of too speedy growth. Germany has traditionally been the bastion of sound money in modern Europe, but the Ukraine situation has presented a new and serious financial challenge. It has both to reduce its dependence on imports of Russian gas and to cover the costs of the intended large increase in defence expenditure. Further, the intellectual argument against monetary financing of budget deficits – expressed too dogmatically perhaps by Bundesbank economists in the early years of the single currency – has been more or less abandoned. Leading figures in the European Central Bank are almost explicit in their scorn for it. In the attached research paper (and again in the monthly video), I discuss how the ECB no longer behaves as if its balance sheet were constrained by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. When Christine Lagarde took over from Mario Draghi as the ECB President, the ECB’s total assets were €4,676 billion. At 11 March 2022 they were almost 86% higher at €8,687 billion.

Third, money growth is also decelerating in the UK. However, this is by accident, not design. The Bank of England’s research publications ignore the behaviour of money aggregates altogether. The February issue of its Monthly Policy Report has a jejune and worthless discussion (in Box C on pp. 31 – 3) of how changes in Bank Rate affect other interest rates, presumably because the senior people at the Bank believe that interest rate changes define the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. The document also has a third chapter, entitled ‘In focus – Wages and Inflation’. Its authors have regressed intellectually to the 1960s and 1970s, when the theory that inflation was caused by excessive wage demands led to wage and price controls, beer and sandwiches at No. 10, the three-day week and other nonsense. (The Germans had their problems in that era, but nothing as daft as beer and sandwiches etc.) The clarification of these issues in the 1980s and 1990s was supposed to have been finalized by the setting of inflation targets in late 1992 and the granting of operational independence to the Bank of England in 1997. Does the Bank of England’s top brass now believe that their institution is not responsible for keeping inflation down? Perhaps so, and it has to be said there are hundreds/thousands of Keynesian economists in this country who agree with them, while many more of these deluded people are churned out by British universities as the years go by.

Poetry and economic commentary may not mix, but the last couple of years have been so ghastly – now culminating in the Ukraine horror – that may I cite Yeats’ 2019 ‘The Second Coming’? Of course the West is right to block Russia from the use of most of its foreign exchange reserves, but the assorted ruffians who “govern” many of the world’s countries will now be increasingly reluctant to buy North American and European government debt (and that of Japan and Australia). As Yeats put it, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed Bin Salman is apparently prepared to sell oil to China in exchange for yuan bank deposits. “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” But MBS is not silly to look askance at the current US inflation rate and the shocking recent financial debauchery in the world’s key power. All the same, Saudi Aramco is increasing investment sharply, to take market share from Russia… So it’s not all bad news.

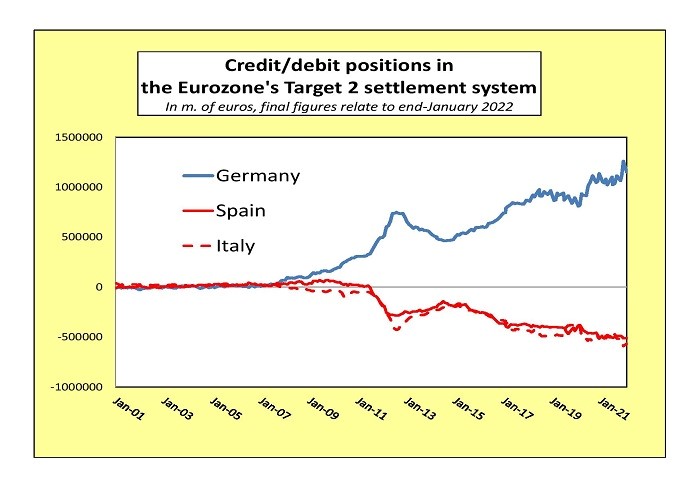

Above is the usual chart on imbalances in the Target2 settlement system. The Bundesbank’s (or Germany’s) credit balance fell back heavily in January to €1,1,49.9b., while the Italian debit balance declined and the Spanish debit balance was stable. Germany and other creditor nations may resent the poor returns on the Target2 assets, but at least the anxieties and tensions are between nations that are very much at peace. The cumulative costs of European monetary integration to Germany would now run to several per cent of one year’s GDP, but it may be viewed as a good investment in a mostly friendly and cooperative continent. (Is Russia still part of that continent?)

………….