Beijing Blues

posted by Karim Pakravan on January 22, 2019 - 11:41am

President Xi will not attend the World Economic Forum’s bash in Davos this year. Two years ago, Xi presented his globalist views as the counterpart to the newly elected President Trump’s populist/protectionist rhetoric. This year, China will be represented by Vice President Wang QiShan, who is expected to face a tougher crowd. In the past year, President Xi and the Chinese leadership have faced new challenges despite an unprecedented consolidation of power since the end of the Maoist era.

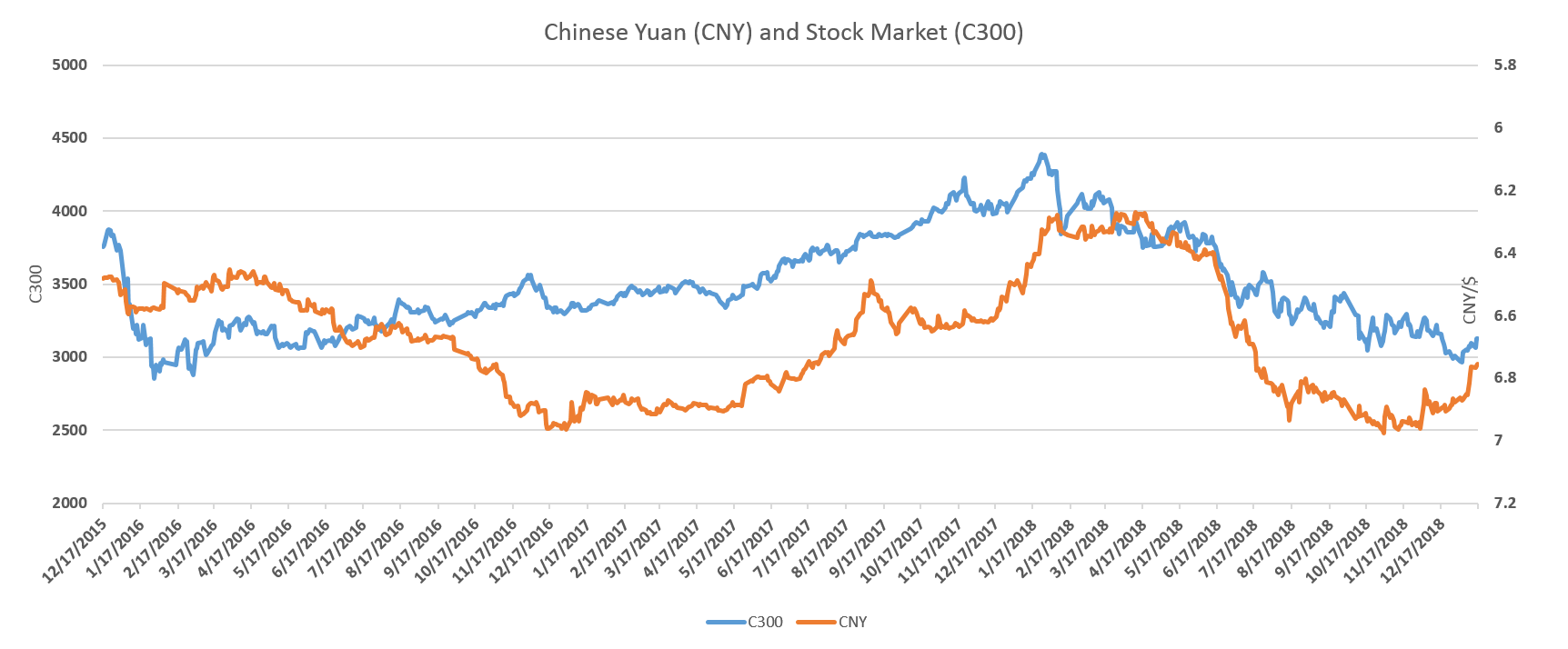

China’s economy has come under pressure in the past few months. Growth has slowed down to a pace of 6.5%-6.8% (annualized), the lowest since the 1990s, exports and imports are stalling, capital flight continues and the current account has slipped in the red in 2Q18 and 3Q18. Manufacturing has stalled, with the Caixin PMI Manufacturing falling below 50 for the first time since April 2018[1]. The CNY has lost 7.2% since its 2018 high in mid-April, and the Shanghai/Shenzen stock market index has dropped by almost 30% in the past year.

The Chinese economic slowdown reflects both cyclical and secular factors. However, the Chinese government’s efforts to stimulate the economy face major structural problems in the Chinese economy.

The global economy has shifted from a synchronized and robust performance in the first half of 2018 to slowing and increasingly divergent growth in the second half. The U.S. economy, pumped up by the fiscal stimulus, accelerated in the second and third quarter of the year, while China, the European Union and Japan all suffered a slowdown—and a brief output contraction in Germany. The IMF is now forecasting a sharper slowdown, with an accumulation of downside risks. The global slowdown has also been reflected in slower growth in world trade, from 4.0% in 2017 to 3.3% last year.

The global tech boom is skidding to an end, with a downturn in the global electronics cycle taking root. The weaker global tech sector has been affecting China, a major production platform for tech components and products.

The United States started a trade war with China, putting tariffs on $250 billion worth of Chinese exports to the United States (about half of the total), and threatening to put tariffs on the remainder if a new trade deal is not reached. After the Trump-Xi summit at the G20 meeting in November, the two sides agreed to start negotiation. The Trump administration agreed to defer increasing tariffs from 10% to 25% for until March 2.

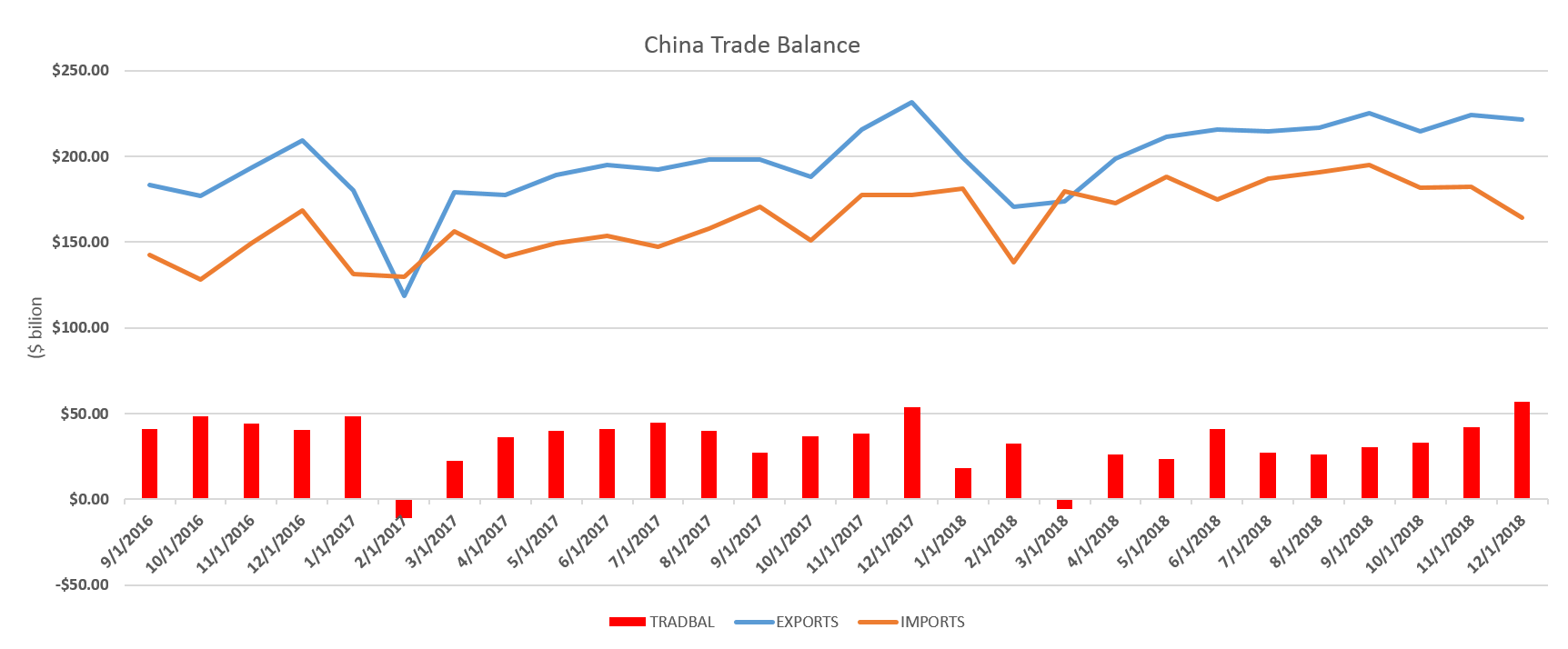

While the tariffs have added to China’s economic woes, the impact has yet to be felt. Both Chinese exports and imports contracted sharply in December. However, we have yet to see a major impact of U.S. tariffs on Chinese exports-- exports and imports where both up for the year,rising by respectively 9.9% and 15.8% (from 6.9% and 16.1% the previous year. At the same time, the Chinese trade surplus with the United States climbed to $323 billion in 2018, its highest level since 2006.

The trade negotiations are complex and unlikely to be resolved soon. However, the Chinese are making small concessions to placate President Trump, going as far as pledging to bring down the US-China trade deficit to zero in six years. Nevertheless, fear of damaging further the slowing global economy could restrain the United States, and more drastic trade actions by the Trump administration are likely to be postponed beyond the March 2 deadline.

China is also facing pushback from other major Western countries. First, the major European countries face the same problems as the United States regarding Chinese restrictive trade policies. Second, they are concerned about the fact that Chinese concessions to the United States will divert even more Chinese exports to Europe. Finally, the Europeans and the Japanese are equally concerned as the United States about the national security and economic aspects of China’s push for dominance in the technology field.

The Chinese response to the economic slowdown has been a standard one: pumping more liquidity in the banking system, cutting taxes and pumping up infrastructural spending. However, these policies are having diminishing marginal returns, and most likely will contribute to a further accumulation of debt in an already highly leveraged economy.

The consolidation of power in the hands of President Xi (who does no longer face any term limits), as well as those of the Communist Party reflect a return to centralized economic decision and an end to economic reforms. In the absence of structural reforms, the Chinese economy will depend on increased state intervention, further debt accumulation and massively expensive projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative.

[1] PMI stands for Purchasing Managers Index. This measure is a forward-looking survey, with the cut-off point between expansion and contraction at 50.